Text passages

-

Frontispiece. (inscription on pedestal)

Appears to be

Μη[?]δεν Κάλλιον ἢ[?] πάντα ειδέναι.

Nothing more beautiful than to know everything.

But if those are really etas, they certainly look unusual. See also maxim attributed to Plato on page 2.

-

Appears to be

Hæc est Diaphanti nobilis Mathematici τέχνη ἐπιζευτικὴ, quâ ex paucis, iisque lumine natutæ notis principiis, altissima quævis Arithmeticæ, & Geometriæ sacramenta aperit, tantâ mentis fæcunditate, auantâ nobis monumenta ejus sat, superque demonstrant.

This is the art of [? combinations ?] of the noble mathematician Diophantus, by means of which, from a small number of principles, considered in the light of nature [?], he uncovered the highest secrets of arithmetic and geometry; with what great fertility of mind [he did so], his works sufficiently and more than sufficiently demonstrate to us.

Translating lumine natutæ as in the light of nature entails a conjecture that natutæ is a misprint for naturæ. It seems more likely that it's just a form whose morphology I am having trouble recognizing. (Along with Morpheus and Parsley and the other Latin morphological analysers I've tried.) I also confess to uncertainty about the construction of the second half of the sentence.

Kircher glosses (another form of) the word ἐπιζευτικὴ on page 25 (see below).

For ἐπι- cf. Copley, leftmost column; Kooy, RGreekL Latin Supplement (sic) code 178

For -ευ- cf. Copley, leftmost column; Kooy, RGreekL Latin Supplement (sic) code 179.

For -τ- cf. Copley, rightmost column (τι); Stephanus (screen 3 of 8); Kooy, RGreekL Latin Supplement (sic) code 245.

-

Page 2: chapter 2, column 1: quotation from Plato.

Appears to be

Cum teste Platone, μηδὲν γλύκυον ἢ πάντα εἰδέναι, nil dulcius sit, quàm omnia scire, ...

As Plato witnesses, nothing is sweeter than to know all things, ...

See also frontispiece of the book, where the sentiment attributed here to Plato is carved (in a variant formulation) on the pedestal.

-

Page 3: chapter 2, column 2, line 2:

Appears to be

... quis dubitabit, nisi ἄλογος, mentem hominis, rationis ductu ad omnium dictarum rerum scientiam sese extendere posse, ...

... who will doubt, except a [blockhead? an irrational person?], that the human mind is capable, when led by reason, of encompassing all of those things mentioned ...

-

Page 3: chapter 3, column 2: Ramon Llull as Doctor Illuminatus.

Appears to be

... Quos inter primum non immeritò locum obtinet Raymundus Lullus, quem alii ob excellens ingenii, quo præstitit, lumen Θεοδίδακτον, sive divinitus illuminatum Doctorem appellant.

... Among whom Raymond Lull justifiably takes pride of place, whom (on account of his excellent, outstanding mind) some call the divinely Enlightened Doctor.

-

Page 5: chapter 3 (top part of page), column 1, line -1; column 2, line 3:

Appears to be

... Verumtamen sicuti per Metaphysicos & abstractos intellectualium combinationum recessus abditas ad scientiarum conquisitionem semitas ἀκριβεσέρως indagat, ita quoque non cuivis datum est hanc adire Corinthum, nisi is insigni Metaphysicæ, abstractarumque conitionum πανοπλία instructus fuerit, ut proinde aliquando Herculei ingenii virum extiturum confidam, qui reclusas sub eo latentes gazas ad usum convertat, mediocrium quoque ingeniorum capacitati accommodet.

-

Page 6: top, column 1, line 1

Appears to be

... adeóque ἀδύνατον sit, ut quispiam in ulla facultate quicquam laude dignum præstet, nisi priùs scientiam, de qua tractat, eximiè calleat, Dialecticæ quoque institutionem non ignoret.

-

Page 13: column 1. This is obscured in the Wolfenbüttel image, but can be seen in the Google Books copy. The Wolfbenbüttel copy seems to indicate that the book was sold with the inner circles of figure 4 printed on a separate piece of paper, so that they could be cut out and pinned to the page (as seen in the Vienna copy) and the reader could rotate the circles as prescribed by Llull and Kircher.

Appears to be

... arduum tamen omninò ne dicam ἀδύνατον existimo, ...

... I regard it, however, as altogether laborious, not to say [? impossible ?] ...

-

Page 14: column 1, bottom

Appears to be

Atque hæc est methodus à Lullo præscripta, pulchra sanè, & quæ ingenium sapiat, si terminorum reducibilium applicationem clariùs & ευμεθοδέρως docuisset.

And this is the method prescribed by Lull, very pretty to be sure, and with a hint of genius, if he had taught the the application of reducible terms more clearly and [? methodically ?].

-

Page 25: Book 2, part 2, chapter 6; column 2 (top), line -6.

Appears to be

Horum naturæ principiorum usum ad omnium notitiam primò per circulos, de inde quoque per tabulas combinatorias, quas græcè ἐπιζευτικὰς vocant, exhibebimus.

We shall show the use of these principles of nature first by means of the circles, and then also by means of the tables of combinations, which are called in Greek ἐπιζευτικὰς.

-

Page 80: column 2, line 2.

Appears to be

1. Hinc sequitur, hallucinari omnes eos, qui animæ essentiam definièrunt per motum aut quietem, & Platonem secuti, αὐτοκίνητον se ipsa mobilem dixerunt. Exsibilandi quoque Democritus & Leucippus, qui animam igneæ naturæ esse, & ex igneis atomis conflatam asseverârunt; Si enim igneum corpus est, quomodò spiritualis substantia? Si αὐτοκίνητος sive seipsam movens, minimè distinguetur à brutis, cùm spiritus vitales & animales in utroque sint.

From this it follows that all those who would define the essence of the soul by means of movement and rest, and who following Plato call it able to move by itself, are dreaming. Democritus and Leucippus are also drifting off course; they have averred that the soul is of an igneous nature, and put together from atoms of fire. For if the soul is a fiery body, how can a substance be spiritual? If it is autokinetic, moving by itself, then it hardly distinguishes itself from brutes, for vital and animal spirits are present in both.

-

Page 101: Liber III, Præfatio, line -5.

Appears to be

Non ignoro complures fuisse, qui Universalem Artis Lullianæ, quam pollicetur, methodum, non dicam utilem aut fructuosum in scientifico negotio, sed verbo παράδοξον καὶ ἀδύνατον existimarint, fieri non posse rati, ut ad tam pauca principia, tanta scientiarum amplitudo & varietas adaptetur.

I am aware that there have been many who have (I should say) regarded the promised universal method of the art of Lull as being not useful and fruitful in scientific work, but in a word ... (incredible and impossible?), reckoning that it is not possible from such a small number of principles to develop such a wealth and variety of sciences.

-

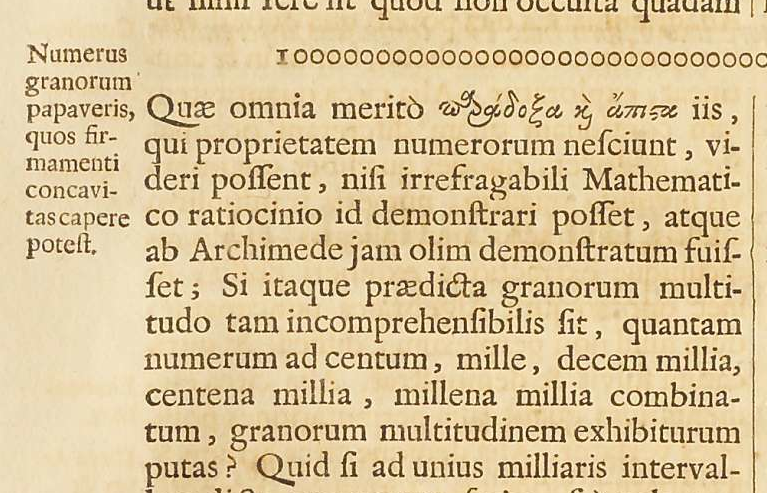

Page 154: top half of page (above the number 10E50 in middle of page), column 2, line -9.

Appears to be

... Mirantur multi in ripa maris aut in deserto quopiam fabuloso arenæ multitudinem, quam fieri non posse putant, ut sub numerorum leges cadere queat, quod tamen tantum abest ut ἀδύνατον sit, ut nihil potius Combinatoriæ Artis magis quadret, quam non tantùm omnes & maris & desertorum fabulosorum arenosos montes sub numerum cogere, set quotnam eorum universæ Telluris concavum; dicam amplius, totius firmamenti vacuitas capax sit, numero & quidem non nisi unitate & 50 Cyphris expresso, exhibere, sequens exemplum demonstrat:

-

Page 154: bottom of page (below the number 10E50 in middle of page), column 1, line 1.

Appears to be

Quæ omnia merito παράδοξα καὶ ἄπις[?]α iis, qui proprietatem numerorum nesciunt, videri possent, nisi irrefragibile Mathematico ratiocinio id demonstrari posset, atque ab Archimede jam olim demonstratum fuisset; ...

-

Page 214: column 1, middle, in list opposite marginal note 7 Gradus appetitivæ facultatis.

Appears to be

Quoniam verò intellectiva vis sine appetiviva [sic] nihil exequitur; hinc voluntatem, qui appetitus rationis est, semper eum concomitari necesse est; utpote sine qua ad agendum non impelleretur; cujus septem gradus sunt, ut sequitur.

- Primus est Voluntas finis, seu ejus rei quam volumus, & βούλησις Græcis dicitur, seu volitio.

- Secundus dicitur à Philosopho ζήτησις καὶ σκέψις. Inquisitio & Consideratio, qua ad id, quod nescimus, cognoscendum impellimur.

- Tertius βουλὴ dictus, & est consilium, quo deliberamus, an rem aggredi conveniat, an non.

- Quartus γνώμη seu sententia, qua id, quod affectamus, & probamus, judicio nostro approbamus.

- Quintus προαίρεσις, et dicitur delectus, quo id quod melius est, eligimus, & electio quoque dicitur.

- Sextus ὀρμὴ sive profectio dicitur, & est instar stimuli, quo ad agendum & prosequendum incitamur.

- Septimus est χρη̃σις sive usus, quo in re, quam appetivimus, cognita, veluti bono adepto quiescimus, sive qui est finis cognitionis.

-

Page 244: column 2, line 4 after heading Consectarium.

Appears to be

Hinc sequitur, omnia quæ in Universitate rerum sunt, aut corporea esse aut incorporea, aut ex corporeo & incorporeo composita; Quæ omnia ἀναλυτικο-συνθετικω̃ς ita deduco.

-

Page 283: column 2, line 6.

Appears to be

Quæ moles crescet, si accesserint variæ figuræ Syllogismorum, per propositiones absolutas, conditionatas, universales, particulares, affirmativas, negativas, quæ omnia fusè demonstrata sunt, in 4. Lib. prioris Tomi, uti & in Logica Combinatoria, ad quam Lectorem remitto. Unde hoc loco tantùm κατὰ την ἰσαγωγην, ex singulis Combinationum Abacis, nonnullas propositiones adducemus, ut Lectori uberrimam demus cæterarum rerum deducendarum materiem: Ex hisce enim tabulis quisque pro libitu suo applicare poterit, quæ profectui suo magis profutura cognôrit.

[For ην see Copley. But what are grave accents doing over ν?]

-

Page 327: top half of page, column 2, line -4.

Appears to be

Atque hæc est totius Metaphysicæ contemplationis ἀνακεφαλαίωσις quædam, quam ideò fusius tractandum suscepimus; ut per ea Artista ad nostræ Metaphysicæ præcepta aptior reddatur.

-

Page 341: column 2, line -4.

Appears to be

Accipe ex Tabula Combinatoria Universali Fol. 179. quascunque literarum triades, sive perpendiculariter, sive transversim, sive διαγόνως dispositas. Ex Abaci primi Tabula prima Combinatoria excipe Columnam secundam, uti hîc apparet:

[For δια see Copley.]

-

Page 367: Caput II., Paradigma I., column 1.

Appears to be

Desumpsimus paradigmatis argumentum ex Hippocratis Aphorismo 10. Sect. 2. ubi sic dicit Medicorum parens.

Τὰ μὴ καθαρὰ τ̃ σωμάτων ὁκόσον ἂν θρέψης, μα̃λλον βλάψεις.

Non pura corpora quotiescunque nutriveris, iis magis nocebis.

-

Page 376: column 2, line -12 before Quæstio II. (Context: discussion of the relation of justice to various relative principles.)

Appears to be

In Coelis exactam motuum rationem, quæ non est aliud, nisi adequatissima justitia perpetua & constans, quâ motus veloces & tardi ad admirabiles justitiæ æquitatisque leges, ad effectus à natura intentos producendos reducuntur. Comparet & hoc in elementorum, in mixtorum productione, temperie & ἐυκρασία. De homine jam diximus.

-

Page 432: middle part of page, column 2, line 2.

Appears to be

Atque hic dicendi modus, quem Rhetores artificialem dicunt, nos Proteum appellamus Rheoricum in omnes formas convertibilem, verbo παντόμορφον.

-

Page 458: middle of page, second bracketed list, line 6 (under alpha).

Appears to be

De effectibus miris phantasiæ in mulis, in pica muliebri, quam Græci κίτταν vocant.

-

Page 459: column 1, line 31 (paragraph "Et sic de cæteris", line 6).

Appears to be

Et sic de cæteris: De duratione, potentia, instinctu, appetitu, virtute, veritate, gloria, differentia, concordantia, contrarietate, causis, mediis, fine, &c. quæ omnia more solito examinata, totam exhaurient de doctrina somni philosophiam, ὀνειρομαντείας sive divinationis specierum per somnium, causas & principia aperient; ubi de somniis supernaturalibus, diabolicis, naturalibus, magnus campus disceptandi. Sed ne opus in immensum crescat, hîc calamum sistendum duxi.

It's page 459. Now he starts to worry?